Leptospirosis update!

Leptospirosis, commonly called “Lepto” is a complex and important disease in the New Zealand (NZ) farming industry. Its importance is two-fold, firstly due to the impact it can have on infected animals and, secondly, because humans can be infected causing severe and even life-threatening disease.

As a disease, Lepto is complicated; the intricacies of which we won’t go into here, suffice to say that when a “maintenance” host is infected they don’t get sick or show signs of infection but when an “accidental” host is infected they do get sick and show symptoms.

In recent years our knowledge of Lepto has seen some important developments. Some of these have come from the Leptospirosis Working Group at Massey University that was created to investigate concerns about the increased number of human cases being seen by medical professionals. This rise in cases was thought to be in relation to the shedding of infective leptospires in the urine of vaccinated dairy cows. The Group conducted a large 200 herd, 4000 cow, survey that found 27% of herds (being one in fourty cows at an individual level) had at least one cow actively shedding leptospires in their urine. In 74% of these shedding cows they found what was initially thought to be Leptospirosis tarassovi (L. tarassovi) antibodies. However, on closer examination a new serovar that had very similar, but distinct, characteristics to L. tarassovi was unveiled and is being called Leptospirosis pacifica (L. pacifica). The conclusion was that L. pacifica prevalence is high in dairy herds in NZ, giving the suggestion that there was likely a link between the increase in cow shedding of L. pacifica and the increase in human Lepto cases.

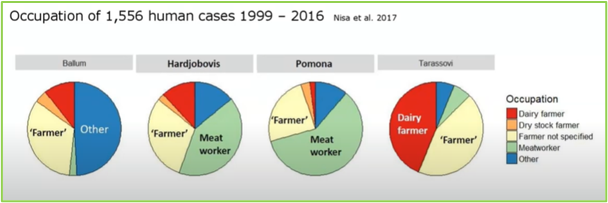

Diagram 1: Public health surveillance data from ESR showing that L. tarassovi cases (that we now know are actually L. pacifica) are strongly represented among dairy (and other not specified “Farmers”) workers.

At this stage it appears that cattle are the maintenance host (it has not yet been found in wildlife) for L. pacifica and do not show clinical signs. However in humans, as an accidental host, the disease can be severe. Reported symptoms are varied from typical Lepto symptoms of fatigue, high temperature, hallucinations and severe headaches, through to less commonly associated symptoms of nausea, diarrhoea and abdominal pain to coughing, sore throat and rib pain… this variability leading to a likely underdiagnosis of L. pacifica infection, with the suggestion that it could even be confused with COVID-19.

Lepto vaccination of cattle is a cornerstone to preventing human disease. From a Health and Safety perspective, it is a key part of minimising the risk to farm workers. In the past NZ cattle, particularly dairy herds, have been routinely vaccinated for Lepto which has successfully and significantly reduced the risk of Lepto in the human population until recently. However, the current vaccines contain only two or three Lepto strains but do not include L. tarassovi which we now know is required for cross protection against L. pacifica.

The good news is that there is a new vaccine, Lepto 4-WayTM, that has been developed, by drug company Virbac, in response to the emergence of “Pacifica”, which will be available from early 2024. The benefit of this being that L. pacifica has the same surface antigens as L. tarassovi, which means that cattle will respond by making antibodies to L. tarassovi that will also convey protection against L. pacifica. The “4-way” vaccine is named as such as it contains four serovars, all of which have been identified to cause disease in livestock and humans in NZ - L. hardjo, L. copenhageni, L. pomona and now L. tarassovi. It has no added adjuvant, meaning reduced injection site reactions, and can be used in at-risk calves from four weeks of age. Cattle require a primary 2ml injection under the skin in the upper neck, with a further dose (booster) of 2ml given four to six weeks later and then an annual booster given thereafter. There are no with-holding periods.

Introduction of Lepto 4-way can be done how best suits each farm… from vaccinating all classes of cattle twice, four to six weeks apart (quickest and safest but more cost up-front) to using a phased approach over a number of years by using new vaccine on young stock (slower with interim risk period but cost is spread). Don’t hesitate to give your Vet a call to talk through what the best approach might be for your situation.